By Paul Edward Parker | Providence Journal

CRANSTON − Joseph Reek was sleeping 16 hours a day. He had no energy. His kidneys were failing, a complication of Type 2 diabetes. It would take a miracle to save him from dialysis – or worse.

Little did he know that he would find that miracle and the solution under his own roof. But it was a miracle from half a world away that took more than a decade to manifest itself.

Flash back to 2011 in Brazil.

Nilson DaSilva, from the city of Maceia, was a high school principal. But not just any high school principal. He was chosen as the best in his state, a designation that earned him a Fulbright scholarship to come to Florida for two months.

DaSilva wasn’t confident in his English skills, so he turned to an internet penpal site to meet Americans. “I’m going to the U.S. I should at least learn, make some friends,” DaSilva told The Providence Journal this month.

That’s how he met Joseph Reek, who grew up in Cumberland, and the two began communicating through video chats on Skype. Their friendship quickly grew, leading to visits in each other’s countries.

Reek said he knew something deeper was going on. “I knew when I met Nilson he was going to be my partner. Period.”

On Jan. 6, 2014, Reek and DaSilva were married. Since coming to the United States, DaSilva has gotten his U.S. citizenship, as well as bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and is finishing up his Ph.D.

Who will donate a kidney to Reek?

When Reek, 69, realized last year that he was going to need a kidney transplant, a candidate was obvious: his brother, John Reek.

Some 25 years ago, their mother, Patricia Hogan, had donated a kidney to their sister, Linda.

“It’s family, and that’s how we were brought up,” John Reek, in his 50s, told The Journal.

The younger brother started going through the screening process to get cleared to donate.

But, at a meeting in late summer with doctors, bad news: John Reek didn’t qualify to be a donor. The doctors asked whether Joseph Reek had another donor in mind.

“I raised my arm,” DaSilva recalled the moment, “and said, ‘Me.'”

DaSilva, 49, began the screening process, which normally takes months.

“He was very committed to the donation,” said Dr. Basma Merhi, one of the team of doctors at Rhode Island Hospital that worked with Reek and DaSilva. “He was very eager to donate to his husband.”

Two weeks after the process started, DaSilva got a call while at work at Pawtucket’s Shea High School, where he teaches Portuguese. “Nilson,” the member of the transplant team told him, “Mr. Reek can receive your kidney with no damage to him.”

DaSilva let the office at the high school know: “I have to go home right now because I have to tell my husband that I will donate my kidney.”

DaSilva has more than just medical concerns

Nilson faced a complication most organ donors don’t have to contend with: He wanted to tell his students about what he was about to do. “As an educator, I had a mission to tell people that it’s important to donate an organ.”

But he was hesitant because he wanted to tell the whole story about who would receive his kidney, which would mean coming out as a gay man. He didn’t know how his students would react.

He went about it in stages, first telling them he was going to donate a kidney. Then he told the rest of the story.

“They said, ‘Mr. DaSilva, you are a hero,'” he told The Journal.

The kidney is transferred from one man to the other in near-simultaneous surgeries

On Jan. 8, Reek and DaSilva walked into adjoining operating rooms in Rhode Island Hospital for surgeries that would be almost simultaneous. DaSilva’s procedure, lasting about two and a half hours, began first, followed quickly by Reek’s.

One of DaSilva’s kidneys was removed in a minimally invasive laparoscopic nephrectomy, the technical term for removal of a kidney.

At the same time, Reek’s body was being prepared to receive DaSilva’s kidney.

The kidney doesn’t wait very long, Merhi said. “Usually, it’s very, very quick. It comes from one room to the other” in about 10 minutes.

Then the surgical team had to make three connections to Reek’s new kidney:

The artery that brings blood to the kidney, which filters out the waste material.

The ureter, which carries away waste material in the form of urine.

And finally, the vein, which carries the filtered blood back to the rest of the body.

Reek really wants a burger

Two days after the surgery, even though his body still needs months to fully heal, Reek was done with the hospital. “I was up and I wanted out.” Plus, he had a craving for a burger.

The husbands were staying in separate rooms, but hospital staff brought them together for dinner. And Reek got his burger.

Now, he’s looking forward to returning to his work as a massage therapist. And DaSilva is looking forward to his return to the classroom, both as a teacher and as a Ph.D. student.

“The hospital gave me 12 weeks, but I don’t think I’ll need 12 weeks,” he said. “I’ll be back this school year for sure.”

Still, Reek faces a lifetime of taking medication to prevent his body from rejecting his husband’s kidney. Even if he takes his medicine as scheduled, there is a 10% risk of rejection, according to Dr. Merhi. But, because he received a kidney from a live donor, the organ should last 15 to 20 years, perhaps longer. If it had been harvested from a cadaver, that probably would be 10 to 12 years, she said.

So far, there have been no complications. “Your whole body and everything changes,” said Reek. “I’ve never felt better in my life.”

Dr. Merhi hopes Reek and DaSilva’s story will spur others to consider donation, either directly to a loved one or in an exchange program, where donors who don’t match medically with a loved one can donate to someone else in exchange for another donor giving to the loved one.

“We need more living donors to step forward,” the doctor said. “Living donation is safe. There’s always anxiety about living with one kidney.” But it comes with a big payoff, she said. “They’re saving a life. They’re giving the gift of life.”

And, in the case of DaSilva and Reek, there’s even more.

“It shows how much he loves him,” Merhi said. “It’s a great love story.”

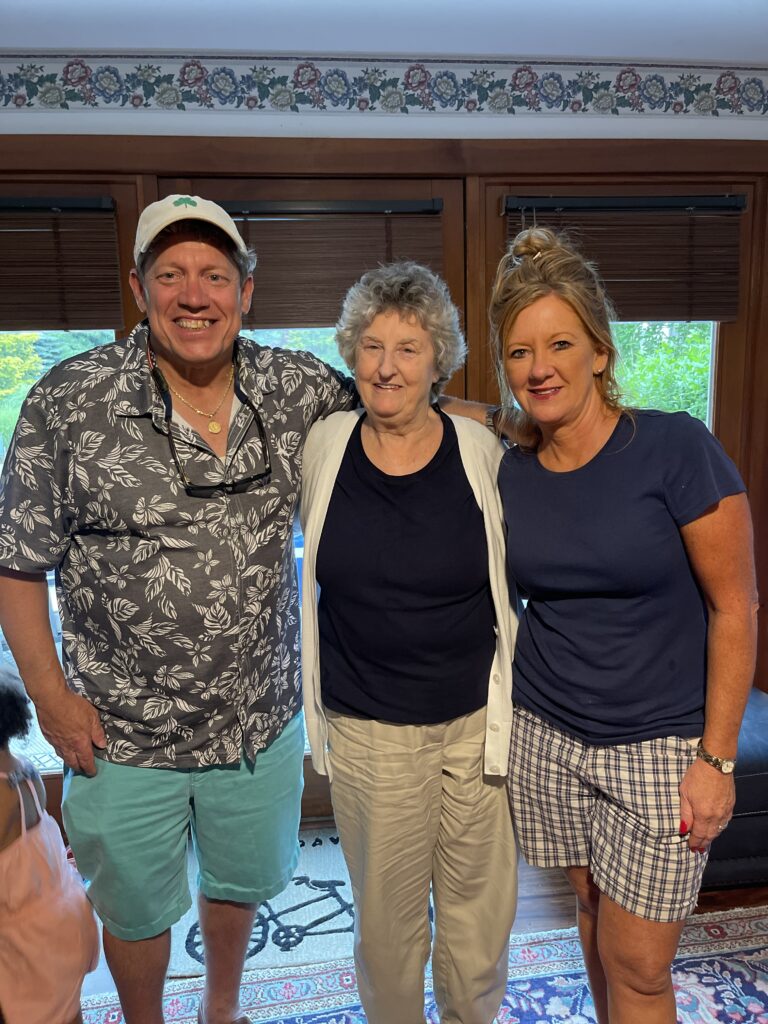

Joseph Reek, left and his husband Nilson DaSilva, have dinner together in

RI Hospital 2 days after they had surgery for DaSilva to donate a kidney

to Reek. Photo provided by Nilson DaSilva

Article by Paul Edward Parker, The Providence Journal, 1/23/2024