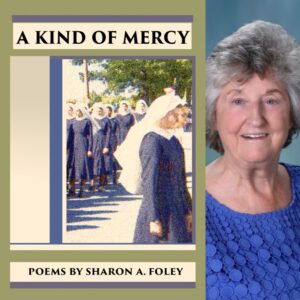

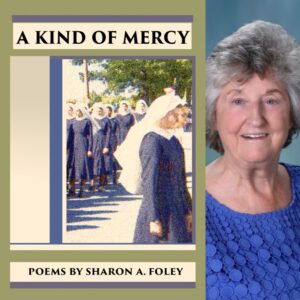

I’m so pleased to announce that my chapbook, A Kind of Mercy, is now on sale through Finishing Line Press. The following is the direct link: https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/a-kind-of-mercy-by-sharon-a-foley/

I’m so pleased to announce that my chapbook, A Kind of Mercy, is now on sale through Finishing Line Press. The following is the direct link: https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/a-kind-of-mercy-by-sharon-a-foley/

Chatham Rose McCloskey, my sister Maureen’s granddaughter, graduated from Emmanuel College today. I had the pleasure of watching her graduation in real time through virtual streaming, and seeing photos posted on Facebook by her mother,

Tracey McCloskey. Chatham’s spirit shines forth–her vibrancy, sincerity, and beauty.

She had the honor of being the President of her Class of 2025. On her gown, she wore a pin of her father, Ken McCloskey, holding her as a baby. I’m sure Ken was present, bursting with pride of his daughter. Chatham’s extended family on her maternal side were present, glowing with pride. Her cousin, Sarah Cabral, was also present, recalling their childhood ties. My sister Maureen holds all in a heart full of love. We are so grateful!

Chatham Rose McCloskey, Graduate of Emmanuel College, 5/10/2025

RUMFORD — Waiting is never fun, but in some cases the stakes are high indeed.

For the 295 Rhode Islanders waiting for a kidney transplant as of May, 2024, the three- to five-year wait to find a donor match – and in the best case, a living donor – can be fraught with anxiety. It’s a wait that Sharon Foley of St. Margaret’s Parish in Rumford walked into three years ago when a bit of vertigo led her to visit her doctor.

A basic kidney workup showed a function of below 20. The normal kidney function range is between 20 and 80.

The diagnosis of stage 4 chronic kidney disease changed Foley’s life in an instant. But aside from the vertigo, she had no other symptoms – a situation she says is common in kidney disease.

“When I was younger, I was on a medication for 20 years,” Foley said. “The medication scarred my kidneys. The damage had been done much earlier in life.”

It was only in 1992, when Foley had been taking the medication for 17 years, that a nutritionist did a hair analysis that showed the danger the medication was posing to her health; but, she said, he did not make the connection to kidney damage. She then worked with her doctor to come off of the medication and credits her nutritionist with unknowingly saving her kidneys from continued damage, but by then the devastation had been wrought.

Because the kidneys’ function is to filter impurities from the blood, impaired kidney function negatively impacts all other organs. The kidneys also produce hormones that “help control the blood pressure, stimulate the bone marrow to produce red blood cells, and absorb calcium from food in order to strengthen bone,” according to the website of the Living Kidney Donor Program at Rhode Island Hospital. Healthy kidney function is vital to survival.

Foley was put on a waiting list for a living kidney donor two years ago. Since her initial diagnosis, her disease has progressed to stage 5.

Why such a long wait for a donor?

“You’re asking a huge commitment from somebody,” Foley said. “You’re asking somebody to give up a part of their body.”

A living donor is optimal, Foley said, because a kidney transplant has a better chance of success when the organ comes from a living person. According to the Cleveland Clinic website, kidneys from living donors have a functional life of between 15 to 20 years, as opposed to the 10- to 15-year lifespan of kidneys from deceased donors. There is also a much higher chance that a living donor’s kidney will start functioning right after transplant, reducing or eliminating the need for dialysis.

Foley said that in her experience, people who have been kidney donors view the experience as an overwhelmingly positive one, the “wonderful experience of saving someone’s life.”

Many potential donors, both friends and complete strangers, have contacted Foley with their willingness to donate; but each time something has caused the plan to fall through. Even though about 25 percent of the population is willing to donate, Foley said, the challenge lies in finding a good match.

But Foley isn’t just sitting around waiting. She’s become a vocal advocate for raising awareness of the need for living kidney donors, arranging a workshop titled “Lives Forever Changed: Stories of Hope and Compassion” at Cranston Public Library in May, 2024. About 50 people attended the workshop, said Foley, which included speakers who had both given and received living donor kidneys. Dr. Basma Merhi, Medical Director of the Living Donor Program at Rhode Island Hospital, opened the workshop with an overview of the importance of donation and the requirements that living donors must meet.

“I do get tired,” she said. “But it doesn’t prevent me from doing my work. I’m very fortunate that it doesn’t interfere with anything in my daily life right now.”

Yet as time passes without a transplant, Foley may eventually have to go on dialysis and her kidney disease can become terminal.

“If I don’t get the transplant my life will be shorter than if I do get the transplant,” she said.

Foley has been planning another “Lives forever Changed” workshop to take place at the Seekonk Public Library on March 26.

“It’s really important to get the word out there because it’s not understood easily,” she said, emphasizing that being a living donor is more than a good deed – it’s a calling.

“We don’t think of the need for self-sacrifice in this manner,” she said. “It’s kind of a radical thing.”

To learn more about the Living Donor Program at Rhode Island Hospital, visit https://www.brownhealth.org/centers-services/transplant-center/living-kidney-donor-program or call 401-444-8562 or 1-888-444-0102.

If you would like to find out if you might be a good living kidney donor for Sharon Foley, visit www.sharonneedsakidney.org or email SharonNeedsaKidney@gmail.com.

By Kathleen Troost-Cramer, Rhode Island Catholic Correspondent

Sharon Foley, a parishioner of St. Margaret Parish in Rumford, has been diagnosed with stage 4 chronic kidney disease and is hopeful that a living donor may feel called to help change her life.

Photo courtesy of Sharon Foley

Rhode Island Catholic, February 6, 2025

I’m still searching for a living kidney donor. If you can help, email me at SharonNeedsaKidney@gmail.com

My chapbook A Kind of Mercy is accepted for publication and will be released in September, 2025. These poems take you inside my convent life as a Sister of Mercy.

Go to my website: SharonNeedsaKidney.com to listen to my poem, Year Four, I’m Chief of the Laundry.

I’m still searching for a kidney. Any donor, any age, any blood type will do. If you don’t match me, I’m still eligible for a kidney swap. Share this video of Lives Forever Changed

Lives Forever Changed, 5/29/2024, Cranston Public Library

The educational program on kidney donation, May 29th at the Cranston Public Library was a vibrant event. Here is a highlight video of the event. Please share with many!

An Educational Program About Kidney Donation

DATE: Wednesday, May 29, 2024

TIME: 6:30pm to 7:45pm

LOCATION: Cranston Public Library, 140 Sockanosset Cross Road

FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC

Presenters include Dr. Basma O. Merhi, MD along with a panel of donors and recipients

Lives Forever Changed: Stories of Hope and Compassion: An educational program about kidney donation.

Date: Wednesday, May 29, 2024

Time: 6:30pm to 7:45pm

Location: Cranston Public Library, Central Library, James T. Giles Community Room

Contact: Robin Nyzio, RNyzio@cranstonlibrary.org

To Register: Go to the Cranston Public Library website; click Events

Presenters include Dr. Basma O. Merhi, MD, Brown Medicine Division of Organ Transplantation, Rhode Island Hospital along with a panel of donors and recipients.

Dr. Merhi will provide general information about the Organ Transplantation program, as well as the procedures for both those needing a kidney and those interested in becoming donors. The panel of donors and recipients will tell their particular story about kidney donation. There will be a brief video presentation Donation Myths: True or False by Marian Charlton, SRN, Clinical Manager of Living, Donor and Paired Donation Program at Hackensack University Medical Center. In addition, there will be time for questions and answers. Flyers and pamphlets will be available as well.

I still search for a living kidney donor, and along the way of this search I am blessed.

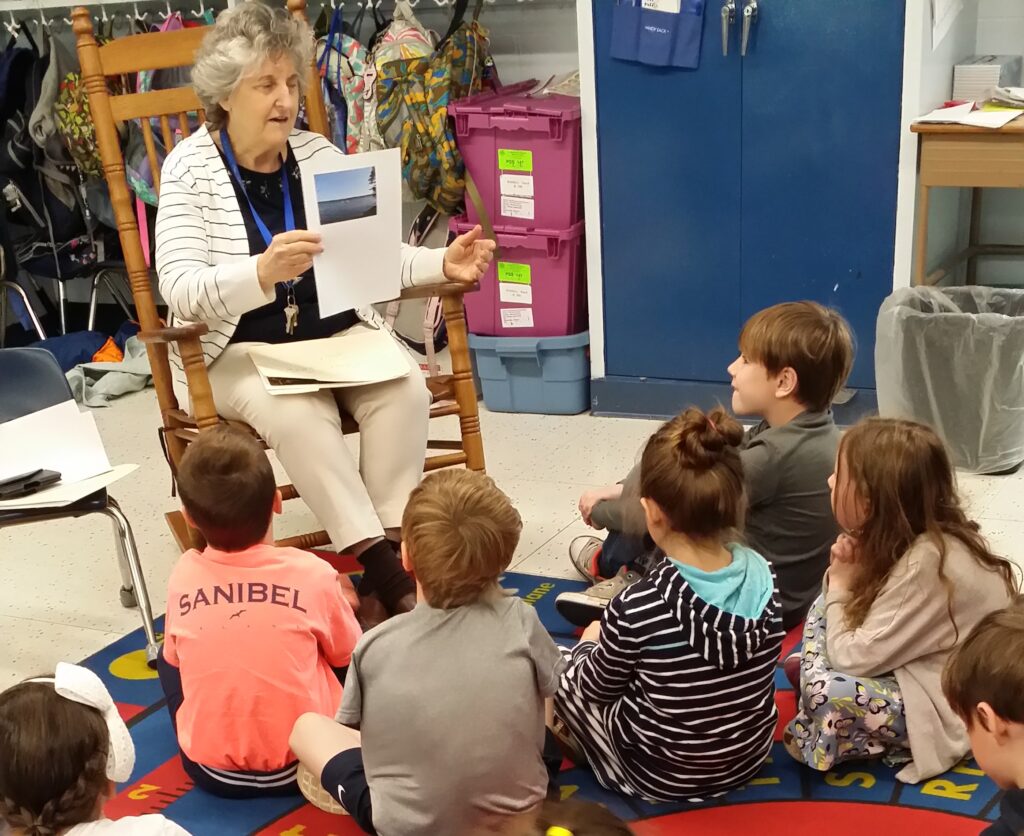

I must have done something good because today as I fumble to pay my parking ticket at the RI Hospital kiosk I hear a clear voice, “Can I help you?” As I turn around, the woman startles when she sees who I am. I recognize her also but I can’t recall how. She gives me the key: her son Jack. Then it all falls into place —the years when as the school social worker I spoke with her nearly daily, giving reports of how Jack was adjusting to the school day. Together we had worked so closely to help Jack stay in school each day. He’s now a senior in high school and she wants to invite me to his graduation party. Of course I will go. With some hesitancy, I gather courage to let her know that I have chronic kidney disease, stage five, and that I’m searching for a living kidney donor. “Can you help?” I ask. Without any hesitancy, she texts me her email address. Something good happens.

Sharon Foley as a school social worker, teaching a lesson to first grade students on finding a safe spot.

Today we celebrate St. Brigid. Her feast day marks the end of the darkness of winter and heralds the new season of hope and growth. Brigid is the patron saint of poets and is known for her miracles of healing for the disenfranchised. I pray that Brigid will inspire someone to be a living kidney donor for me and for all others who are waiting for a kidney. I wrote the following poem about St. Brigid.

On St. Brigid’s Day

I hold a relic, a sliver of her bone,

no bigger than a hangnail

wrapped like a badge

the edges stitched with green thread

to help me quell

my fear of lightning.

I weave Brigid’s cross today

press firmly my fingers on the straw

crisscrossing and turning them

to make the central knot

to seek her heart, that heart that heard anomalies

like lepers thirsty

who want to celebrate with beer,

and the woman who did not want

her child, I pray let me hear

and heal.